When LLM Success Becomes the Enemy of Adoption

15.01.2026

TL;DR: If you work with people from around the world, The Culture Map by Erin Meyer is well worth your time, especially if you lead a global team or rely on cross-cultural collaboration for success. It reveals how deeply our cultural background shapes how we lead, communicate, and build trust. Ignoring that can lead to misjudgments, miscommunication, and missed opportunities.

I usually pack a book or two when I travel, and for our family trip to Japan, I chose The Culture Map by Erin Meyer. It felt like a fitting choice - and a refreshing shift from the communication-focused books I’d been reading and listening to lately. Ironically, I only started reading it on the flight home, but finished it the very next day.

Although I strongly recommend reading the book in full, I’ll share a summary of the main ideas, along with a few personal reflections from my own experience working in a culture different from the one I was born into.

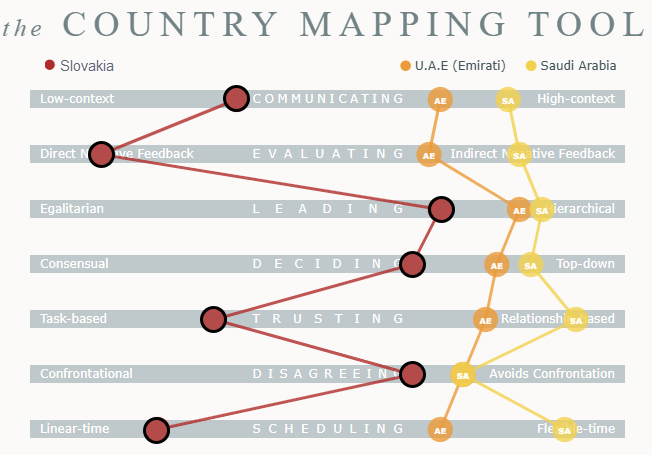

Erin breaks down cultural differences into eight distinctive dimensions:

While each of us has unique personality traits that influence how we communicate or make decisions, The Culture Map focuses on patterns shared by cultural groups - often shaped by a country’s history, philosophical traditions, religion, and generational norms.

Coming from Slovakia and having worked in the Middle East for the past 12 years, some differences are hard to miss.

In Slovakia, direct negative feedback is quite normal, though it's typically delivered in private. In the GCC, however, it's often better to soften the message and balance it with positive context to preserve harmony and avoid loss of face.

Another notable difference lies in scheduling. In Slovakia, we tend to follow linear-time thinking, though not as strictly as cultures like Germany, Switzerland, or the UK. Deadlines are seen as fixed milestones, and any change is a big deal. In contrast, the GCC operates on a more flexible-time model, where timelines are fluid and adaptability is expected.

One aspect I used to overlook is how relationship-based cultures are in the Middle East - and much of Asia. In Slovakia, work and personal life are kept separate. Workplace trust is built through performance and consistency. In the Middle East, however, trust is deeply personal - it grows through shared meals, coffee chats, and informal conversations just as much as through formal meetings.

It’s important to note that these observations apply "on average." Company culture can significantly skew some of these dimensions. For example, while Slovakia is shown on Erin Meyer’s “Leading” scale as more hierarchical than egalitarian, the US-based company I worked for in Slovakia had a very flat structure. There was no issue with going directly to the country manager to discuss matters, even without informing your direct supervisor.

Another crucial insight: it’s not the absolute position of a culture that matters most, but its relative position compared to yours. We interpret others' actions and communication through the lens of our own cultural norms. Recognizing that lens is the first step to seeing more clearly.

One of the most powerful ideas I took from The Culture Map is the reminder that our behaviors - especially at work - are often shaped by the culture we grew up in. These patterns feel so natural, we don’t even notice them.

It’s like the story of the young fish who swims past an older fish who asks, “How’s the water?” The younger one replies, “What’s water?”

Culture is our water.

If we’re unaware of it, we risk misjudging others who are simply doing their best, just in ways shaped by different norms. What might seem disorganized, evasive, rude, or too formal could be someone operating within their own cultural comfort zone and following the rules they’ve learned to obey.

As professionals - especially in global teams or client-facing roles - being aware of cultural preferences doesn’t just help reduce friction, it’s essential.

---------------------------------------------------